Root Rot: Spot and Fix

Root rot is the silent assassin of the plant world. It doesn’t announce itself with wilting leaves or dropping stems until the damage is nearly irreversible. One day your plant looks fine, and the next, it’s collapsing despite having wet soil.

I’ve learned that by the time you see the symptoms above ground, the battle below the soil surface has likely been raging for weeks. The good news is that if you catch it before the entire root system is compromised, you can usually save the plant. I’ve brought back several from the brink, including a snake plant I was convinced was a goner.

Let me walk you through how to spot root rot and what to do about it.

Identifying mushy black roots

Section titled “Identifying mushy black roots”Healthy roots are firm and white, or sometimes light tan. When you gently squeeze them, they feel solid, kind of like a fresh carrot stick. Rotting roots are the opposite. They’re soft, mushy, and dark brown or black. If you squeeze them, they might fall apart in your hand or leak gross brown liquid.

The first sign something is wrong usually happens above the soil. Your plant might start looking wilted even though the soil is wet. The leaves might turn yellow, especially the lower ones. Sometimes you’ll see brown spots or the leaves just look generally sad and droopy. I had a philodendron that kept losing leaves one by one, and I didn’t realize what was happening until I finally checked the roots.

To actually look at the roots, you need to unpot the plant. I know this feels scary if you’ve never done it before, but it’s really not that bad. Take the plant to your sink or bathtub (trust me, this gets messy). Tip the pot on its side and gently wiggle the plant out. If it’s really stuck, you can run a butter knife around the inside edge of the pot.

Once you have the root ball out, look at what you’re working with. If the soil is soaking wet and smells funky, that’s your first clue. Gently shake off some of the soil so you can see the actual roots. This is where you’ll know for sure.

Healthy roots will be light colored and firm when you touch them. Rotting roots look completely different. They’re dark, almost black, and when you touch them they feel squishy. Sometimes they’re so far gone that they’ll just slide off in your hand like wet tissue paper. I’ve had roots that literally disintegrated when I tried to rinse them.

According to research from the University of Maryland Extension, root rot is most commonly caused by overwatering and poor drainage, which creates the perfect environment for fungi like Pythium and Phytophthora to thrive. These fungi attack the roots and basically turn them into mush.

One thing that confused me at first is that not all dark roots are rotting. Some plants naturally have darker roots, and older roots can be tan or light brown. The key is the texture. If they’re firm, they’re probably fine. If they’re mushy, they’re rotting.

The ‘Rot Smell’ test

Section titled “The ‘Rot Smell’ test”This is going to sound weird, but rotting roots have a very specific smell. Once you’ve smelled it, you’ll never forget it. It’s kind of like a wet basement mixed with compost that’s gone bad. Earthy, but in a sour, unpleasant way.

I learned about this the hard way with a jade plant. I kept thinking the soil just smelled like normal wet dirt, but my roommate walked by and said, “Something smells rotten.” She was right. When I finally unpotted it, the smell hit me immediately. It wasn’t just damp soil, it was that distinct rot smell.

Fresh, healthy soil smells clean and earthy. It’s a pleasant smell, the kind you get after rain. Rotting roots smell musty and slightly sweet in a bad way. Some people compare it to sewage, though I think that’s a bit dramatic. To me, it’s more like vegetables that have been sitting in the back of the fridge too long.

When you unpot your plant, lean in and take a sniff. I know this sounds gross, but it’s actually one of the fastest ways to diagnose root rot. If the soil smells off, you’ve probably got a problem. If it smells like normal dirt, you might be dealing with something else.

The smell comes from the fungi and bacteria breaking down the root tissue. According to information from the Penn State Extension, these pathogens thrive in oxygen-poor, waterlogged conditions. As they decompose the roots, they release gases that create that characteristic smell.

I’ve also noticed that the smell gets worse the longer the rot has been going on. A plant that’s just starting to develop root rot might not smell that bad yet. But a plant that’s been sitting in soggy soil for weeks will reek when you pull it out of the pot.

Sometimes you can smell the rot even before you unpot the plant. If you lean down close to the soil surface and catch a whiff of something funky, that’s a bad sign. I had a prayer plant that I kept smelling something weird around, and sure enough, when I checked the roots, half of them were rotted.

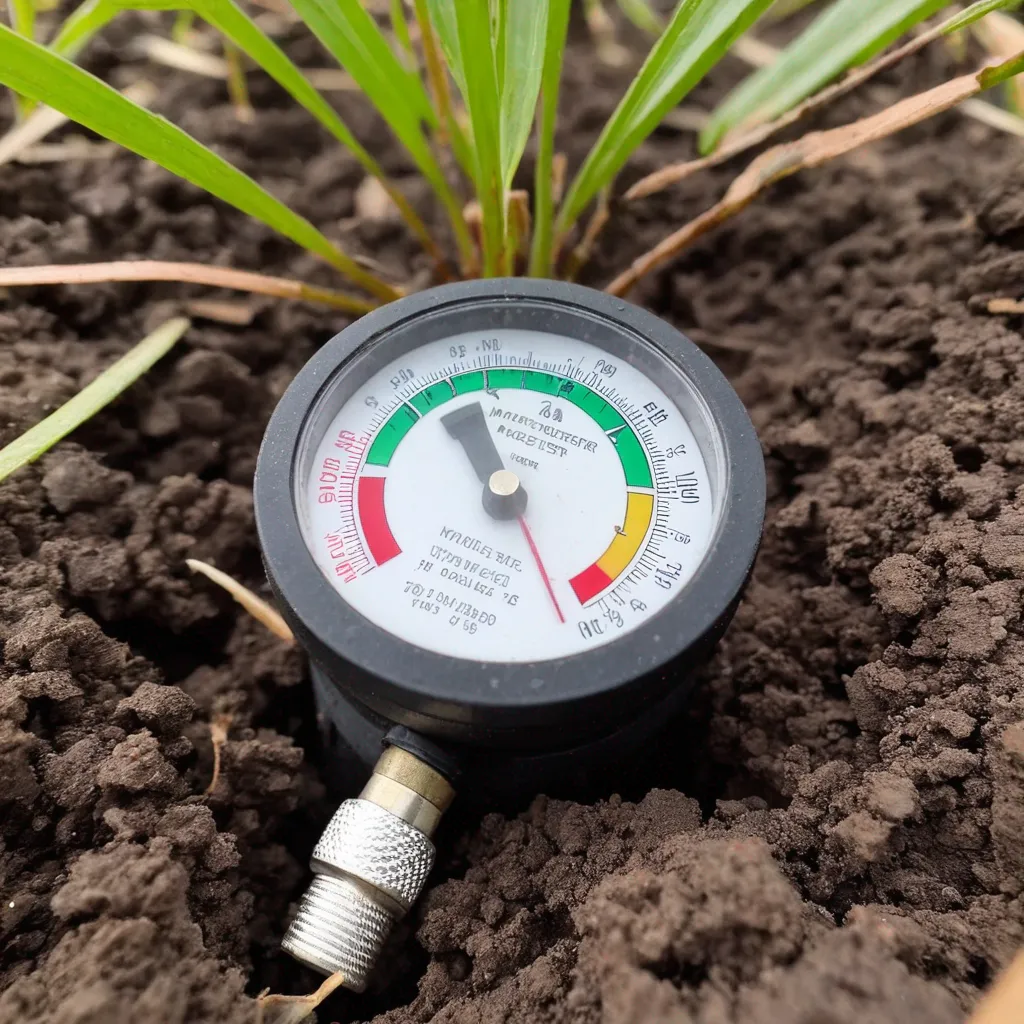

Above: A close up look at the symptoms.

Above: A close up look at the symptoms.

Using Hydrogen Peroxide

Section titled “Using Hydrogen Peroxide”Hydrogen peroxide is my secret weapon for root rot. I’ve used it to save probably a dozen plants at this point. It works because it kills the fungi and bacteria causing the rot, and it also adds oxygen to the soil, which helps the remaining healthy roots.

You want to use the regular 3% hydrogen peroxide that you can buy at any drugstore or grocery store. Don’t use the stronger stuff, you’ll burn the roots. I learned this from a Cornell University publication on treating root diseases.

Here’s what I do. First, I remove all the obviously rotted roots. Get a clean pair of scissors or pruning shears (I wipe mine down with rubbing alcohol first) and cut away anything that’s black, mushy, or slimy. Be ruthless about this. It’s better to cut away too much than to leave rotting tissue behind. I know it feels scary to cut away so much, but healthy roots will grow back. Rotting roots will just keep spreading the problem.

Once I’ve trimmed away all the bad roots, I rinse what’s left under lukewarm water. This gets rid of any remaining soil and lets me see if I missed any rotted sections.

Then comes the hydrogen peroxide treatment. I mix one part hydrogen peroxide with two parts water in a bowl or bucket. So if I use one cup of peroxide, I add two cups of water. Some people do a 1:1 ratio, but I’ve found that 1:2 works fine and is gentler on the roots.

I submerge the roots in this solution and let them soak for about ten minutes. You’ll see it start to bubble and fizz, especially if there’s still some rot present. That’s the peroxide doing its job, killing off the bad stuff and releasing oxygen. It’s kind of satisfying to watch, honestly.

After the soak, I rinse the roots one more time with plain water to wash away any dead tissue that the peroxide loosened up. Then I let the roots air dry for about an hour. I usually just set the plant on a towel and go do something else for a bit. This gives any remaining hydrogen peroxide time to evaporate and lets the cut ends dry out slightly, which helps prevent new infections.

Some people also water their plants with diluted hydrogen peroxide after repotting, but I usually don’t bother. The initial treatment has always been enough for me.

Repotting into fresh soil

Section titled “Repotting into fresh soil”After you’ve treated the roots, you need to repot the plant. Do not put it back into the same soggy soil. That’s just asking for the rot to come back.

If the pot itself seems fine (it has drainage holes and isn’t too big), you can reuse it, but wash it thoroughly first. I scrub mine with dish soap and hot water, then let them dry completely. If the pot was part of the problem (no drainage holes, or way too big for the plant), get a new one.

For soil, use fresh potting mix. Don’t reuse the old soil, even if it looks okay. It might still have fungal spores in it. I’ve made this mistake before and watched the rot come right back within a few weeks.

The type of soil matters. Regular potting mix is fine for most plants, but if you’re dealing with a plant that’s prone to root rot (like succulents, cacti, or snake plants), mix in some perlite or coarse sand to improve drainage. I usually do about 1 part perlite to 2 parts potting mix. This creates more air pockets in the soil so water drains faster.

According to the University of Minnesota Extension, proper drainage is critical for preventing root rot. The soil needs to allow excess water to drain away while still holding enough moisture for the roots.

When you’re ready to repot, put a layer of soil in the bottom of the pot, then position the plant so the roots can spread out naturally. Don’t pack them in or twist them around. Fill in around the roots with more soil, gently pressing down as you go to eliminate air pockets, but don’t compact it too hard.

One thing I’ve learned is to plant at the same depth as before. Don’t bury the stem deeper than it was originally. This can cause stem rot, which is just as bad as root rot.

After repotting, I don’t water right away if the roots were really damaged. I wait a day or two to let any cuts heal. If the plant had plenty of healthy roots left, I might give it a light watering just to settle the soil, but I’m very careful not to overdo it.

Above: The tools you need to fix this.

Above: The tools you need to fix this.

Preventing future rot

Section titled “Preventing future rot”Honestly, preventing root rot is way easier than treating it. Once I figured out the main causes, I stopped killing plants with overwatering.

The biggest thing is learning to water properly. I used to water on a schedule, like every Sunday, but different plants need different amounts of water, and the same plant needs different amounts depending on the season. Now I check the soil before I water. I stick my finger about two inches down into the soil. If it feels damp, I don’t water. If it feels dry, I water.

For plants that like to dry out more between waterings (succulents, snake plants, ZZ plants), I wait until the soil is dry almost all the way to the bottom of the pot. For plants that like consistent moisture (ferns, calatheas), I water when the top inch or so is dry.

I also learned that pot size matters a lot. A plant in a pot that’s too big will sit in wet soil for too long because there aren’t enough roots to absorb the water. I used to think bigger pots were better because the plant had more room to grow, but that’s not how it works. Now I only go up one pot size when repotting, maybe two inches larger in diameter at most.

Drainage holes are not negotiable. I don’t care how cute a pot is, if it doesn’t have drainage holes, I either drill some or use it as a decorative outer pot with a smaller nursery pot inside. Water needs somewhere to go. I’ve tried the “just water carefully” approach with no-drain pots, and it always ends badly.

The type of pot matters too. Terracotta pots are great for plants prone to root rot because they’re porous and let moisture evaporate through the sides. Plastic pots hold moisture longer, which is fine for some plants but risky for others. I keep my succulents and snake plants in terracotta and my pothos in plastic.

Room temperature and light also affect how fast soil dries out. In winter, when my apartment is cooler and there’s less light, my plants need way less water. I’ve killed plants by watering them the same amount in January as I did in July. Now I adjust based on the season.

Finally, I’ve gotten better at recognizing early warning signs. If leaves start looking weird or the plant seems off, I check the roots before things get bad. It’s much easier to fix a small problem than to save a plant that’s mostly rotted.

Root rot used to stress me out so much. I thought once a plant had it, it was basically dead. But now I know it’s usually fixable if you catch it early and act fast. I’ve saved plants that I was sure were goners, and they’re thriving now. If you think your plant has root rot, don’t panic. Just follow these steps, be patient, and give it a chance to recover.

References

Section titled “References”University of Maryland Extension. “Root Rots.” Home and Garden Information Center.

Penn State Extension. “Houseplant Diseases.”

Cornell University. Department of Horticulture. “Root and Stem Rots.”

University of Minnesota Extension. “Houseplant root rot and overwatering.”